When Alison asks me if I’d like to write something about my favourite short story, J. D. Salinger’s ‘For Esmé –with Love and Squalor’ immediately comes to mind, even though I’ve not read it for a long time.

Most of you will probably have heard of J. D. Salinger (1919 – 2010), who was the American author of a classic novel of teenage angst called ‘The Catcher in the Rye’, published in 1951. The narrator, Holden Caulfield, is a 17-year-old American boy who thinks life is ‘lousy’, everything is ‘crumby’ and that ‘phoney bastards’ abound.

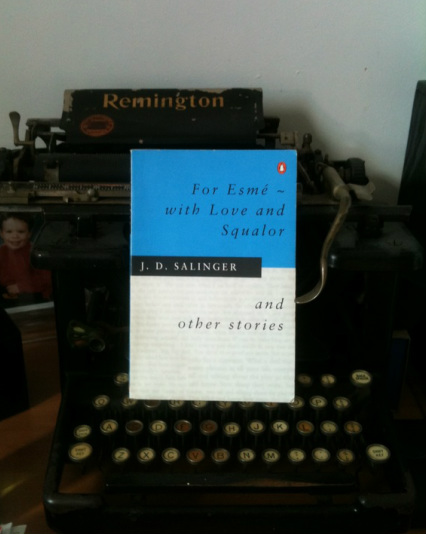

Salinger’s short story collection was published next, in 1953. Originally titled “Nine Stories’, the UK edition was called ‘For Esmé – with Love and Squalor’.

When I first read these short stories, many years ago, I loved them, especially the title story. In fact, one of the first short stories I ever wrote is called ‘Esmé’s Weekend’ – as a little homage to Mr. Salinger!

However, on 30th March, when I see the note in my diary – ‘Write something for Alison’ – I begin to feel anxious. Maybe, when I read ‘Esmé’ again after all these years I’ll feel differently about it.

I can’t remember anyone mentioning the story in any workshop or short story conference I’ve attended. Maybe it’s twee, or old hat, or just not as good as I remember it.

Instead of actually doing any actual writing, therefore, I procrastinate…

I check my emails, I faff around on Facebook, and as I trawl around the Internet, I’m delighted to discover that the Irish writer Kevin Barry has won the 2012 Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award with the hugely enjoyable story ‘Beer Trip to Llandudno’.

I decide to read the on-line article about the six writers shortlisted for the award. Each of them was asked to cite their favourite short story collection. One of them, Tom Lee, has chosen ‘For Esmé – with Love and Squalor’. How serendipitous!

(Note to self: must read Tom Lee’s début collection, Greenfly.)

Heartened by this pleasant synchronicity, I search the bookshelves for my own copy of ‘Esmé’. My books were once – only once, very briefly – in roughly alphabetical order, so it takes a while.

Finally I relocate it. I read the title story first. It’s so good that I decide to read the entire collection again…

Now, as I read, I realise that Salinger’s stories don’t always adhere to the classic ‘arc of the short story’. They are, nonetheless, wonderful.

The seond thing that strikes me, as an older reader, is that the characters, both adult and children, are psychologically complex and often isolated in some way. It seems to me that many of them possess traits indicative of what’s now called Asperger’s Syndrome. The sensitivity of the little boy in ‘Down at the Dinghy’ is one example. Teddy, in the final story, is a gifted child who exhibits slightly obsessive behaviour. Esmé herself is a little quirky. So is the narrator in ‘De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period’. I could go on…

Though Hans Asperger identified and gave his name to this syndrome in 1944, it was not standardised as a diagnosis until 1994, so it seems very unlikely that Salinger had any specific knowledge of it, or of what we now call ‘the autistic spectrum’. Nonetheless, these stories lead me to speculate that Salinger may have known people with Asperger’s syndrome, or may possibly have been an ‘Aspie’ himself.

I should point out that I’m not an expert in this field; these are just my own musings. Asperger’s Syndrome and the autistic spectrum cover a wide range of behaviour. The terms are not magic formulas and I’m not keen on labels, per se. Sometimes, however, diagnoses are useful as a means of understanding people and if this helps people to reach their full potential, that can only be good.

The Internet is not a reliable expert either… but I type in ‘Aspergers Syndrome J. D. Salinger’ and search all the same, just for interest. Sure enough, I get a few hits from sites like www.aspiesforfreedom.com, which indicate I’m not the only one who’s wondered this. There’s some debate too, as to whether Holden Caulfield, the sensitive and troubled 17-year-old in ‘Catcher in the Rye’, might have fitted into the Asperger’s category.

The fact that Salinger became a recluse in his later years may also be a hint. On the other hand, his experiences in World War II affected him emotionally, resulting in what was post-traumatic stress disorder these days. Perhaps it was this that caused Salinger to seek solitude in later life, rather than Asperger’s Syndrome.

The third thing that I begin to muse on is the fact that I’ve just used the Internet again. I wonder what old Salinger would think of this new world of Twitter and Facebook, emails and blogs? Would he enjoy it all or would he consider it to be ‘lousy’, ‘crumby’ and teeming with ‘phonies’? Somehow, I can’t imagine him tweeting.

But I’m here to talk about the title story in his collection, so here goes...

The facts of ‘For Esmé – with Love and Squalor’ are reasonably straightforward.

The narrator receives a wedding invitation. Because he won’t be able to attend the wedding, he decides to write ‘a few revealing notes about the bride’, as he knew her six years ago (1950).

The story then moves backwards, from 1950 to 1944. The narrator is an American soldier in a top secret training program in England. Bored and lonely he wanders into town and ends up in a tea-room where he meets thirteen-year-old Esmé and her brother, five-year-old Charles. They ignore their governess’s disapproval and come over to his table to chat with him. Esmé is polite, talkative and precocious. She and the narrator discuss the war, her deceased parents, and her plans for the future. The narrator jokes with Charles, who’s a giddy little boy. He notices that Esmé’s wearing a rather large watch. She tells him it belonged to her deceased father. Esmé discovers that before the war, the narrator considered himself a writer. She requests that he write a story exclusively for her sometime, but not something childish and silly. ‘Squalor. I’m extremely interested in squalor,’ she says. After exchanging addresses, Esmé wishes him luck in the war and, quite formally, tells him that she hopes he’ll emerge with all his faculties intact. Then the children leave.

The story then moves forward in time to several weeks after VE Day (8th May 1945). It seems that Sergeant X (the narrator, ‘cunningly disguised’) has not, in fact, emerged from the war with all his faculties intact. He’s stressed and nervous and may be on the verge of a complete nervous breakdown. His comrade, Clay, tries but fails to talk him out of his depression. Then Sergeant X receives a package which has been readdressed several times. It’s from Esmé. She has sent him her father’s watch as a lucky talisman. When he reads her letter, something changes inside Sergeant X and finally he feels he’s going to be able to sleep. The chance meeting with Esmé and the arrival of her package at just the right time gives him the sense that he might be okay after all.

I’m hugely relieved to be able to say that I still love this story. It’s a strangely uplifting tale and by the time I get to the last page, I’m almost in tears.

A lesser writer might have made this story into a novel. There’s a lot going on.

In ‘Esmé’, the narration changes during the story from first person to third person. This can work in a novel but rarely works in a short story. Somehow, it works here.

The structure of the story is unusual too. The film-maker Jean Luc Godard famously said, ‘A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order.’ Films can work well that way, and so can novels. Generally speaking, however, there’s not enough ‘space’ in a short story to allow the writer to mess around with time. Again, this story confounds that notion. ‘Esmé’ begins at the end of the tale, moves on to the beginning and ends in the middle. Somehow, in spite of this, it holds together beautifully.

As for themes, there are many. The first that spring to mind are hope, the squalor of war and the nature of love, particularly love in the sense of simple human connection, There are other themes too: literature and writing, youth and naivety, foreigness and otherness… for an in-depth discussion of these I recommend http://www.shmoop.com/for-Esmé -with-love-and-squalor.

There’s great dialogue, too, great scenes and some comedy moments where the narrator wanders in the small English town and meets the children. The writing is clear and simple – anyone could read this – and yet it’s full of emotional complexity.

But why does this story pack such an emotional punch?

When it was first published in 1950 (in The New Yorker), everyone reading it had been affected in some way by World War II, and it really resonated with the reading public. Salinger received more letters about ‘Esmé’ than about any of his other short stories.

In these times, the message in ‘Esmé’ is as welcome as it ever was.

Human beings around the world suffer as a result of war, famine, natural disasters, man-made disasters and poverty. In Ireland, too, we’re exhausted from the grim and dreary grind of a long recession – less dramatic than, say, an earthquake, but very ‘tough going’ nonetheless.

We all deserve an ‘Esmé’ moment. We need to believe that there is always sunshine behind clouds, and that we must not lose hope in the future. ‘For Esmé – with Love and Squalor’ is a story that reminds us that, with a little help from our friends, we humans are a resilient bunch. We’ll be okay. We’ll carry on. This is what we need to believe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed